Water User Charges for Ground Water Extraction

IN NEWS

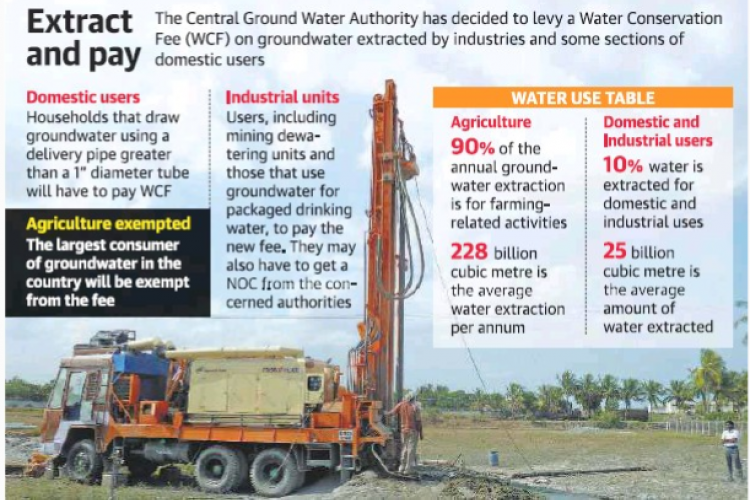

In a bid to promote conservation of groundwater, the Central Ground Water Authority (CGWA) has notified a water conservation fee (WCF) that industries will need to pay on groundwater extraction starting from June.

Industries extracting groundwater including mining-dewatering units and those that use groundwater for packaged drinking water would also need to apply for a no-objection certificate (NOC) from the government.Individual households that draw groundwater using a delivery pipe of a greater than 1 diameter would need to pay a WCF.However, the agriculture sector — the largest consumer of groundwater in the country — will be exempt from the fees. Defence establishments and users who don’t use electricity to extract water have also been granted exemption from the requirement of obtaining NOCs and having to pay the WCF.

The guidelines would come into force with effect from June 2019 and would apply across the country. The government has a list of groundwater blocks, called assessment blocks. These are classified as ‘safe,’ ‘semi-critical,’ ‘critical’ and ‘over-exploited’ depending on the groundwater draft.

SITUATION OF GROUNDWATER IN INDIA

India is the largest user of groundwater in the world, and accounts for about 25% of the global water extraction. The CGWB classifies 6,584 assessment units countrywide. While 1,034 units have been categorised as ‘over-exploited,’ 253 are termed as ‘critical’, 681 as ‘semi-critical’ and 4,520 as ‘safe.’ The remaining 96 assessment units have been classified as ‘saline.’

In India, extracted groundwater is mainly used for irrigation and accounts for about 228 BCM (billion cubic metre) — or about 90% of the annual groundwater extraction. The rest, 25 BCM, is drawn for drinking, domestic and industrial uses.

CAUSES OF EXPLOITATION OF GROUNDWATER

- India’s huge groundwater-dependent population, uncertain climate-reliant recharge processes and indiscriminate land use changes with urbanization are among the many factors that have rendered the Indian groundwater scenario to become a global paradigm for water scarcity, for both quantity and quality.

- The indiscriminate use of rivers and other surface-water bodies in many areas for disposal of sewage and industrial waste has rendered the groundwater non-potable.Ganga water, is the worst of the lot with heavy pollutant load of contaminants like heavy metals sourced from industrial discharge, sewage and open-defecation waste, as well as pesticides and other organic pollutants from agricultural activities.

- Excess water pumping, non implementation of restriction-rules, and unlawful drilling of wells among other factors for the situation causing pollution in groundwater.

- With farmers provided electricity subsidies to help power the groundwater pumping, the water table has seen a drop of up to 4 meters in some parts of the country. This unfettered draining of groundwater sources has accelerated over the past two decades.

- India’s leaders have also been slow or unwilling to adapt to newer technologies or cohesive plans to address the issues.

CONSEQUENCES OF EXPLOITING GROUNDWATER RESOURCES

- Over-exploitation of groundwater resources not only changes soil moisture and land-atmosphere and energy variability but essentially affects the ecohydrological processes of the climate system.

- A lack of groundwater limits biodiversity and dangerous sinkholes result from depleted aquifers.

- Occurrence of salt water contamination as there will be mixing of groundwater with the saltwater .

- Much of the above affects rural citizens where poverty is rampant, but even more developed urban areas face their own challenges.

- Recent drops in manufacturing jobs can be tied to companies being unable to access clean water. Along with the inability to properly cultivate agriculture areas and the water crisis quickly becomes an economic one.

WAY FORWARD

The issue of water sustainability for the years to come centres around critical water sources such as reservoirs and groundwater. The crisis can be tackled by restoring and enhancing groundwater recharge areas, stopping polluted water from recharging groundwater, rainwater and roof top harvesting and the restoration of ponds, lakes and other river systems. The country needs a serious debate about whether to pump their aquifers to the maximum and be very poor thereafter, or manage abstraction for sustainable use. In this process, it should not be forgotten that farmers need to be made more aware of the consequences of imprudent use of groundwater.

However, for more detailed planning, scientifically-prudent, adaptive groundwater management strategies are immediately required to secure, sustain and rejuvenate the accessible, residual, unpolluted groundwater through times of changing socio-economic needs. It is of utmost importance that coordination between different federal and provincial departments that are responsible for planning and management of groundwater resources should be strengthened. Thus, proper, pervasive groundwater governance may optimistically lead to possibilities of transforming the country from a ‘groundwater-deficient’ to ‘groundwater sufficient’ nation, and providing sustainable water availability for about one-fifth of the global population, in not-so-far future.

IAS -2025 Prelims Combined Mains Batch - III Starts - 14-04-2024

IAS -2025 Prelims Combined Mains Batch - III Starts - 14-04-2024