SHALE GAS CHALLENGE

IN NEWS

The Central government approved a far-reaching policy that allows private and government players to explore and exploit unconventional hydrocarbons (including shale gas) in contract areas that were primarily allocated for extracting conventional hydrocarbons.

WHAT IS A SHALE GAS

Shale gas refers to natural gas that is trapped within shale formations. Shales are fine-grained sedimentary rocks that can be rich sources of petroleum and natural gas.

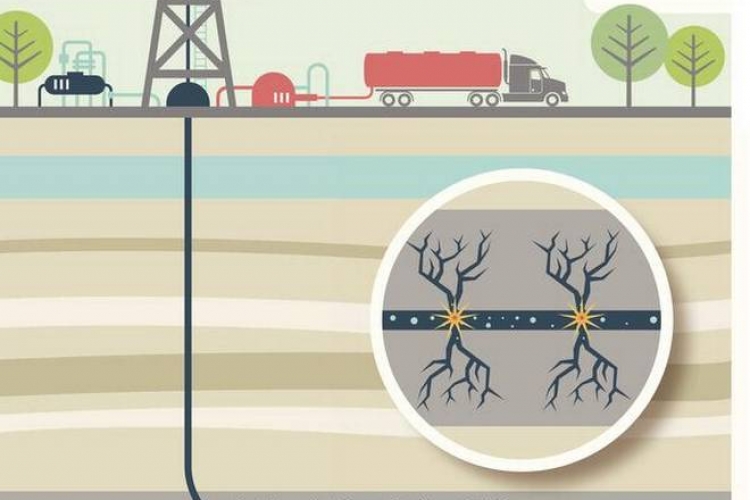

HOW THEY ARE EXTRACTED

Unlike conventional hydrocarbons that can be sponged out of permeable rocks easily, shale gas is trapped under low permeable rocks. Therefore, a mixture of ‘pressurised water, chemicals, and sand’ (shale fluid) is required to break low permeable rocks in order to unlock the shale gas reserves.

The process requires around 5 to 9 million litres of water per extraction activity, posing a daunting challenge to India’s fresh water resources.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

- Shale gas drilling has significant water supply issues. The drilling and fracturing of wells requires large amounts of water. In some areas of the country, significant use of water for shale gas production may affect the availability of water for other uses, and can affect aquatic habitats.

- Drilling and fracturing also produce large amounts of wastewater, which may contain dissolved chemicals and other contaminants that require treatment before disposal or reuse. Because of the quantities of water used, and the complexities inherent in treating some of the chemicals used, wastewater treatment and disposal is an important and challenging issue.

- If mismanaged, the hydraulic fracturing fluid can be released by spills, leaks, or various other exposure pathways. The use of potentially hazardous chemicals in the fracturing fluid means that any release of this fluid can result in the contamination of surrounding areas, including sources of drinking water, and can negatively impact natural habitats.

INDIA S GUIDELINES ON SHALE GAS EXTRACTION

Acknowledging this challenge, the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons (DGH) issued a guideline on environment management during shale gas extraction

- overall volume of fracture fluid is 5 to 10 times that of conventional hydraulic fracturing.

- The guideline states that these challenges will be dealt while granting environmental clearances as per the Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) process.

- The DGH proposes five new reference points (term of references) relating to water issues in the fracking process that a project proponent must explain while applying for the environmental clearance.

- The DGH guideline states that a project proponent must “design and construct wells with proper barriers to isolate and protect groundwater”,

CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE GUIDELINES

- The EIA process, however, does not differentiate between conventional and unconventional hydrocarbons.

- Sensing this regulatory gap, However, these five reference points are not succinct to resolve the water-specific issues posed by the fracking activities. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), which generally releases sector-specific manual for environment clearance, is yet to come out with a manual specific to fracking activities.

- Despite acknowledging the enormity of water requirement for fracking activities, the DGH guideline fails to give a general estimate of water requirement per unit of shale gas over the lifetime of a shale well.

- The importance of clarity in water usage and the place of shale gas extraction in India is linked directly with water requirements of priority sectors like agriculture.

- Shale rocks are usually adjacent to rocks containing useable/ drinking water known as ‘aquifers’. As noted by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 2017, while fracking, the shale fluid could possibly penetrate aquifers leading to methane poisoning of groundwater used for drinking and irrigational purposes. Several researches conclude that such contamination can be controlled, if not avoided, provided a project proponent maintains a distance of 600 m between the aquifers and shale gas fracture zones

- On design of the project proponent,the guidelines misses out on broadly describing the nature or properties of a barrier that can be considered ‘proper’ to isolate and protect the groundwater.

- When shale fluid is injected underground at high pressure to fracture the rock, 5-50% (depending on the local geology) of the fluid returns to the surface, known as ‘flowback water’. Return flows continue as oil and gas is pumped from the well. The flowback water is usually methane-contaminated, and therefore it poses different recycling and leakage issues than usual wastewater. The DGH guideline again touches upon the exclusive nature of the flowback water but neither proposes any substantive treatment method nor recognises the increase in flowback water during repeated extraction of shale gas from a well over a period of time.

- Implementation of the fracking processes without a consultative thought through process, especially on ‘water usage policy’, may result in larger issues including water stress, contamination of groundwater, and related health hazards.

WAY FORWARD

We are missing an opportunity to comprehensively regulate the fracking process for a sustainable shale gas exploration in India. As a first step, a sector-specific EIA manual on exploration and production of unconventional hydrocarbon resources may be a good idea.

IAS -2025 Prelims Combined Mains Batch - III Starts - 14-04-2024

IAS -2025 Prelims Combined Mains Batch - III Starts - 14-04-2024